By Edward Copeland

Three days ago, I celebrated the 40th anniversary of the groundbreaking comedy series All in the Family, which not only addressed issues unheard of for a television comedy, but also introduced dramatic elements to the half-hour comedy format. Ten years and three days later, a drama premiered that almost did the reverse, upending what an hour-long dramatic series could be and injecting a healthy dose of humor, often of the darkest variety, into its story. That series was Hill Street Blues and 30 years later, it's still as strong as it was when it premiered.

When Hill Street Blues debuted, I was in sixth grade and had little use for what passed for hour-long drama at the time. Police dramas were pretty formulaic: crime committed, cops solve crime. Big hour-long shows when I was growing up contained too much goody-goodiness for me (see The Waltons, Little House on the Prairie). The only hour-long show I can recall liking much that wasn't a detective/mystery show was Lou Grant. I didn't tune in to Hill Street Blues

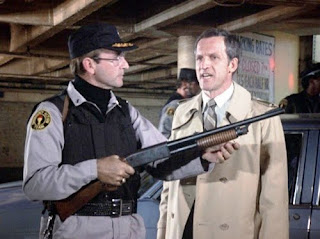

right away, but a classmate sang its praises so I started watching, albeit late, though I caught up with the early episodes in reruns. I was enthralled. The series came to me around the same time that I was discovering Robert Altman in general and his film Nashville in particular. As I've written before, I'm a sucker for large ensemble casts because they seem more realistic to me. My life has lots of people in it, not just a manageable handful. When I saw Hill Street Blues with its opening credits that began with 13 regulars and countless recurring characters (in later seasons, the opening credits would get as high as 17), I knew television had changed. (The photo I used includes Ed Marinaro, though his character, Joe Coffey, didn't appear until the 14th episode of the first season's 15-episode run and he didn't make the opening credits until season 2.) You almost can trace the bounty of quality dramas (albeit non-network ones) that we enjoy on TV today back to Hill Street Blues. Thankfully, it hit the airwaves at a time when the NBC executives in charge then (Fred Silverman, Brandon Tartikoff) actually had patience and kept it on despite miserable ratings. When it swept the Emmys in its first season, the audience began to grow. In fact, Mike Post's memorable instrumental theme became a hit sooner than the show itself, hitting No. 10 on the Billboard Top 100 singles and No. 4 on Billboard's adult contemporary chart in 1981. As much as the Emmys are a joke now, they always will have to earn kudos for saving one of the greatest shows in the history of television.

right away, but a classmate sang its praises so I started watching, albeit late, though I caught up with the early episodes in reruns. I was enthralled. The series came to me around the same time that I was discovering Robert Altman in general and his film Nashville in particular. As I've written before, I'm a sucker for large ensemble casts because they seem more realistic to me. My life has lots of people in it, not just a manageable handful. When I saw Hill Street Blues with its opening credits that began with 13 regulars and countless recurring characters (in later seasons, the opening credits would get as high as 17), I knew television had changed. (The photo I used includes Ed Marinaro, though his character, Joe Coffey, didn't appear until the 14th episode of the first season's 15-episode run and he didn't make the opening credits until season 2.) You almost can trace the bounty of quality dramas (albeit non-network ones) that we enjoy on TV today back to Hill Street Blues. Thankfully, it hit the airwaves at a time when the NBC executives in charge then (Fred Silverman, Brandon Tartikoff) actually had patience and kept it on despite miserable ratings. When it swept the Emmys in its first season, the audience began to grow. In fact, Mike Post's memorable instrumental theme became a hit sooner than the show itself, hitting No. 10 on the Billboard Top 100 singles and No. 4 on Billboard's adult contemporary chart in 1981. As much as the Emmys are a joke now, they always will have to earn kudos for saving one of the greatest shows in the history of television.

One type of television series did use large casts (and had been doing so for decades) and while that genre is often mocked, it doesn't get the credit it deserves, not only for its influence on what made Hill Street Blues different but for what makes most of the finest dramas that have come in its wake so involving. That genre is the soap opera. When Hill Street Blues premiered, nighttime soaps were making a comeback with Dallas, its spinoff Knot's Landing, Flamingo Road and Dynasty, which debuted three days before Hill Street Blues did. (On the comic side, there also was Soap, which I also loved and had a huge cast, though like daytime dramas, its credits were at the end.) In the same time period, networks were reaping big rewards from another format with large casts and continuing storylines: the miniseries. With hits that varied in subject matter as widely as the soapy Rich Man, Poor Man; the fictionalized look at the Nixon White House in Washington: Behind Closed Doors; the historical Backstairs at the White House following eight administrations from the point of view of the servants; and the landmark adaptation of Alex Haley's Roots tracing his ancestors from Africa through slavery until emancipation. These precursors seem to make the time ripe for a series such as Hill Street Blues.

The police drama created by Steven Bochco and Michael Kozoll was the first to take the elements of a soap — large casts, continuing storylines, cliffhangers — and transfer them to a different setting. Instead of the standard relationship drama that you'd find on a soap, Hill Street Blues was the first to camouflage those

aspects in a police story. As Bochco said in a DVD commentary recorded five years ago for the series' premiere episode, "Hill Street Station," he wanted Hill Street Blues not only to be true to the real spirit of police work but to examine the emotional consequences of the job as well. Prior to Hill Street, networks resisted the idea of stories that continued beyond one episode except for special two or three-part episodes for fear that viewers wouldn't make appointment television and the series wouldn't play well in syndication. Once the nighttime soaps showed they could be ratings hits and miniseries showed that audiences would make commitments for an entire week, let alone one night each week, it made the creation of a Hill Street Blues that much easier. Now, more shows, even comedies, contain continuing stories than don't. Some series would mix the continuing stories with standalones such as The X-Files and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Comedies such as Cheers would end each season with a cliffhanger just like Dallas. Larry David would have standalones within season-long arcs, first on the Seinfeld season about Jerry and George writing the TV show and then every season on Curb Your Enthusiasm. Other comedies such as Friends were basically soap operas with laughtracks. All of them, to some extent, owed that freedom to the ground broken by Hill Street.

aspects in a police story. As Bochco said in a DVD commentary recorded five years ago for the series' premiere episode, "Hill Street Station," he wanted Hill Street Blues not only to be true to the real spirit of police work but to examine the emotional consequences of the job as well. Prior to Hill Street, networks resisted the idea of stories that continued beyond one episode except for special two or three-part episodes for fear that viewers wouldn't make appointment television and the series wouldn't play well in syndication. Once the nighttime soaps showed they could be ratings hits and miniseries showed that audiences would make commitments for an entire week, let alone one night each week, it made the creation of a Hill Street Blues that much easier. Now, more shows, even comedies, contain continuing stories than don't. Some series would mix the continuing stories with standalones such as The X-Files and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Comedies such as Cheers would end each season with a cliffhanger just like Dallas. Larry David would have standalones within season-long arcs, first on the Seinfeld season about Jerry and George writing the TV show and then every season on Curb Your Enthusiasm. Other comedies such as Friends were basically soap operas with laughtracks. All of them, to some extent, owed that freedom to the ground broken by Hill Street.As I mentioned in my All in the Family tribute (and other pieces), it usually takes about four episodes for new television series to work their way to what they want to achieve. Hill Street Blues happens to be one of the exceptions as it seems to almost have been born into perfection. Watch its very first episode, "Hill Street

Station," today and it's all already there. According to Bochco on that commentary, many of the series' trademarks that were there from the very beginning weren't planned to be things that would occur in every episode. They didn't originally have a plan to begin every episode with the morning roll call, led in those first three seasons and the early part of the fourth, until actor Michael Conrad's death from cancer, by Sgt. Phil Esterhaus. Neither was it planned for him to end each roll call with what would become the catchphrase, "Let's be careful out there." Some things did get decided based on that excellent template of an episode. Robert Butler, who directed "Hill Street Station" as well as the three episodes that followed, had originally wanted to film the entire episode using hand-held cameras, but Bochco felt it would make it look "too self-conscious." It was agreed though that from that point forward every roll call would be filmed that way. Another decision that was made before the series even hit the air was that each episode would cover one day. Bochco said part of the reasoning for that was to make continuity easier, but it was another nice touch, something that another of my all-time favorite series, Twin Peaks, did (for the most part) during its brief run.

Station," today and it's all already there. According to Bochco on that commentary, many of the series' trademarks that were there from the very beginning weren't planned to be things that would occur in every episode. They didn't originally have a plan to begin every episode with the morning roll call, led in those first three seasons and the early part of the fourth, until actor Michael Conrad's death from cancer, by Sgt. Phil Esterhaus. Neither was it planned for him to end each roll call with what would become the catchphrase, "Let's be careful out there." Some things did get decided based on that excellent template of an episode. Robert Butler, who directed "Hill Street Station" as well as the three episodes that followed, had originally wanted to film the entire episode using hand-held cameras, but Bochco felt it would make it look "too self-conscious." It was agreed though that from that point forward every roll call would be filmed that way. Another decision that was made before the series even hit the air was that each episode would cover one day. Bochco said part of the reasoning for that was to make continuity easier, but it was another nice touch, something that another of my all-time favorite series, Twin Peaks, did (for the most part) during its brief run. Despite its precarious beginnings, ratingswise, Hill Street Blues would go on to last seven seasons and 146 episodes. When I mentioned before that the Emmys helped save it, that was no exaggeration. The size and scope of its impact on the Emmy race the first year it was eligible to compete was so gigantic, that viewers simply couldn't ignore what the Emmy voters were saying. Granted, it helped that this was back when award shows and networks still had sway. Cable still was a fairly small blip and FOX didn't exist, so it basically was

ABC, CBS or NBC or you could read a book (unless you were one of those PBS types). The Emmy broadcast itself drew bigger ratings and when it showered such lavish praise upon Hill Street Blues, it convinced those watching to give the show a chance. It did the same trick a couple years later for a low-rated NBC comedy called Cheers because that network in particular then nurtured quality shows, giving them the time they needed to find their audience instead of killing them quickly when they underperformed. Let me get back to that first Emmy year for Hill Street Blues to illustrate how it basically swallowed most of the nominations (and deservedly). It received 21 nominations and won eight awards including best drama, best lead actor, best lead actress, best supporting actor, best writing and best direction. Its dominance was so great that it took three of the directing, supporting actor and film editing nominations. However, this was nothing compared to what it accomplished in its second season, when it took four out of five of the writing nominations and five out of five of the supporting actor nominations. The first year, its series competition was Dallas, Lou Grant, Quincy and The White Shadow. That second year, it was up against Dynasty, Fame, Lou Grant and Magnum, P.I. Needless to say, in those first few years it wasn't exactly a fair fight, but as other producers and writers saw what television could do, more quality dramas would appear and the network landscape would get markedly better because of the changes brought about by Hill Street Blues. Over its seven seasons, Hill Street Blues earned 98 Emmy nominations and won 25, including four consecutive Emmys for outstanding drama series. Actors who won were Daniel J. Travanti as Furillo (two in a row), Michael Conrad as Esterhaus (two in a row), Barbara Babcock as Grace Gardner, Bruce Weitz as Mick Belker, guest star Alfre Woodard and Betty Thomas as Lucy Bates (who had the unusual situation of an imposter who tried to accept on her behalf and steal the award as she was crossing the stage to get it herself).

ABC, CBS or NBC or you could read a book (unless you were one of those PBS types). The Emmy broadcast itself drew bigger ratings and when it showered such lavish praise upon Hill Street Blues, it convinced those watching to give the show a chance. It did the same trick a couple years later for a low-rated NBC comedy called Cheers because that network in particular then nurtured quality shows, giving them the time they needed to find their audience instead of killing them quickly when they underperformed. Let me get back to that first Emmy year for Hill Street Blues to illustrate how it basically swallowed most of the nominations (and deservedly). It received 21 nominations and won eight awards including best drama, best lead actor, best lead actress, best supporting actor, best writing and best direction. Its dominance was so great that it took three of the directing, supporting actor and film editing nominations. However, this was nothing compared to what it accomplished in its second season, when it took four out of five of the writing nominations and five out of five of the supporting actor nominations. The first year, its series competition was Dallas, Lou Grant, Quincy and The White Shadow. That second year, it was up against Dynasty, Fame, Lou Grant and Magnum, P.I. Needless to say, in those first few years it wasn't exactly a fair fight, but as other producers and writers saw what television could do, more quality dramas would appear and the network landscape would get markedly better because of the changes brought about by Hill Street Blues. Over its seven seasons, Hill Street Blues earned 98 Emmy nominations and won 25, including four consecutive Emmys for outstanding drama series. Actors who won were Daniel J. Travanti as Furillo (two in a row), Michael Conrad as Esterhaus (two in a row), Barbara Babcock as Grace Gardner, Bruce Weitz as Mick Belker, guest star Alfre Woodard and Betty Thomas as Lucy Bates (who had the unusual situation of an imposter who tried to accept on her behalf and steal the award as she was crossing the stage to get it herself).

Not only was Hill Street Blues unlike any drama that had aired on network television before, its large cast lacked anyone who could be called a star or a household name and that's because the show was the star. No one really knew who Daniel J. Travanti was before he appeared in our living rooms as police Capt. Francis Xavier Furillo, assigned to try to keep a handle on the chaotic Hill Street precinct. They couldn't have cast a better center for the show for Travanti was magnificent, miraculously adept at handling both the most dramatic and comic of scenes. In fact, his skills as a deadpan comic on the series may have been unsurpassed. His two consecutive Emmys as outstanding lead actor were quite deserved as he played Furillo, trying to keep peace between rival street gangs, dealing with his ever-present and annoying ex-wife Fay (Barbara Bosson, Bochco's then real-life wife), his own status as a recovering alcoholic (and some falls off the wagon) as well as countless administrative headaches dumped on him by his superiors, especially the recurring character of the politically ambitious Chief Daniels (Jon Cypher).

Travanti's revered Furillo sat at the top of a very talented pyramid of actors playing a collection of diverse and distinctive characters. For those first three seasons and part of the fourth, his right-hand man was Conrad's Esterhaus, his dispatch sergeant and a true original from the moment he appeared, winning him two

consecutive Emmys. Esterhaus' prosaic use of language set him apart from the other characters, though he could be just as rewarding not speaking at all. One of my favorite moments occurred in that first episode as he took Frank's ex Fay aside to try to calm her down after another argument with Furillo. Fay tries to make small talk, asking Phil how his wife is and learns that they also have divorced, but that he's found someone new and she's turned his life around. Fay asks if they plan to wed and Phil tells her that they might after she graduates. Naturally, Fay jumps to the conclusion that Phil, a man well into his 50s, is now dating a college student, but he has to correct her misconception by telling her that his new lady is a senior in high school. Fay collapses in tears and the silent reactions and moves of Conrad's head are hysterical. Phil and the high school senior won't last though, because he will soon meet Grace Gardner (Emmy winner Barbara Babcock). Grace arrives at the precinct by order of Chief Daniels to redecorate the place. At first, Phil finds her a nuisance, but an attraction develops between the sergeant and the widow of a former police officer and before you know it the sexually voracious Grace has enveloped Esterhaus' life.

consecutive Emmys. Esterhaus' prosaic use of language set him apart from the other characters, though he could be just as rewarding not speaking at all. One of my favorite moments occurred in that first episode as he took Frank's ex Fay aside to try to calm her down after another argument with Furillo. Fay tries to make small talk, asking Phil how his wife is and learns that they also have divorced, but that he's found someone new and she's turned his life around. Fay asks if they plan to wed and Phil tells her that they might after she graduates. Naturally, Fay jumps to the conclusion that Phil, a man well into his 50s, is now dating a college student, but he has to correct her misconception by telling her that his new lady is a senior in high school. Fay collapses in tears and the silent reactions and moves of Conrad's head are hysterical. Phil and the high school senior won't last though, because he will soon meet Grace Gardner (Emmy winner Barbara Babcock). Grace arrives at the precinct by order of Chief Daniels to redecorate the place. At first, Phil finds her a nuisance, but an attraction develops between the sergeant and the widow of a former police officer and before you know it the sexually voracious Grace has enveloped Esterhaus' life.

I know I may sound as if I'm repeating myself, but the "Hill Street Station" episode's excellence on so many levels almost makes it worth writing about alone in this tribute. It's a perfect introduction to nearly all the characters (only Betty Thomas' Officer Lucy Bates basically gets silent background shots), it's wonderfully constructed with not one, but two big twists that almost guaranteed the small but discerning number of viewers who were there from the beginning would return for episode two. It's also almost entirely played on a humorous level until more than half the episode is over even though the story has included a tense hostage situation at a convenience store, but before any moment of the standoff can get too serious something always restores the levity. You've got the serious with the conscientious Lt. Henry Goldblume (Joe Spano) trying to talk the two young gang members into releasing their captives and leaving the store and with Furillo back at the station

trying to get their gang's leader Jesus Martinez (the late Trinidad Silva, another wonderful recurring character whose arc through the course of the series amazed) to help the situation. For the funny side, you could always count on James B. Sikking as the pseudo fascist buffoon Lt. Howard Hunter, leader of the precinct's tactical unit. He always recommended overwhelming force no matter what and, without authorization, with Furillo on the scene trying to get the teens to surrender, Howard brings in helicopters that blow everything to hell as his team storms the store and decimate the place. Fortunately, no one dies or is hurt but the store's owner berates Hunter for the destruction. Howard's response is to tell one of his men to check on the owner's immigration papers as he taps his almost-always present pipe against the shop's display window and it shatters. Howard could easily have been a cartoon as could other characters, but as the series went on, they all became terribly and vulnerably human. Howard in particular became multidimensional in later seasons' episodes that found him trapped in the rubble of a collapsed building with another officer (and ugly hints of what he might have done to survive) and when a mistake he made as young officer returns to haunt him and label him as corrupt and he puts a gun to his head, pulls the trigger and the episode ends with the sound of a shot.

trying to get their gang's leader Jesus Martinez (the late Trinidad Silva, another wonderful recurring character whose arc through the course of the series amazed) to help the situation. For the funny side, you could always count on James B. Sikking as the pseudo fascist buffoon Lt. Howard Hunter, leader of the precinct's tactical unit. He always recommended overwhelming force no matter what and, without authorization, with Furillo on the scene trying to get the teens to surrender, Howard brings in helicopters that blow everything to hell as his team storms the store and decimate the place. Fortunately, no one dies or is hurt but the store's owner berates Hunter for the destruction. Howard's response is to tell one of his men to check on the owner's immigration papers as he taps his almost-always present pipe against the shop's display window and it shatters. Howard could easily have been a cartoon as could other characters, but as the series went on, they all became terribly and vulnerably human. Howard in particular became multidimensional in later seasons' episodes that found him trapped in the rubble of a collapsed building with another officer (and ugly hints of what he might have done to survive) and when a mistake he made as young officer returns to haunt him and label him as corrupt and he puts a gun to his head, pulls the trigger and the episode ends with the sound of a shot.

Howard was hardly the only member of the ensemble that risked being a caricature, but Bochco, Kozoll and their team of talented writers and actors took that gamble and that's how they made characters so distinctive from that very first episode and no one proved to be more of an original creation than my own personal favorite, Detective Mick Belker as portrayed brilliantly by Bruce Weitz, who did eventually win an Emmy for the role. Belker looked completely unkempt with his tossled hair and bushy mustache and he often acted as something beyond human, prone to growl to show his displeasure. He took great joy pouncing on perpetrators, often sinking his teeth into them as part of his detention technique. His preferred epithets for people were dogbreath, hairball and dirtbag. Belker had his tender side though, befriending a mentally unbalanced man (Dennis Dugan) who believed he was a superhero from outer space named Captain Freedom (one of many misfits who seemed to be drawn to him over the years) or keeping a pet mouse in his jacket pocket. When it

counted, he still could be a convincing undercover cop and when he was at his desk hunting and pecking out an arrest report on his typewriter, he turned into the good Jewish son when his mother inevitably called to complain about his aging father. (His people skills also turned out to be a family trait, based on the time we met his sister.) In "Hill Street Station," we get to see the first "Hi ma" call with his usual collar and we also get to see the absolute glee on his face when he leaps off a desk to join a pile against a suspect gone mad, even though Furillo warns him, "No biting!" You can see his disappointment as he tells his captain that it isn't fair. "One lousy nose and I'm branded for life." Eventually, without losing his color, he managed to get a wife and child too. I even confess: When I was exiled in seventh and eighth grade in an awful northeastern Kansas town (but isn't seventh and eighth grade hell no matter where you are?), I often growled like Belker at the jerks in junior high.

counted, he still could be a convincing undercover cop and when he was at his desk hunting and pecking out an arrest report on his typewriter, he turned into the good Jewish son when his mother inevitably called to complain about his aging father. (His people skills also turned out to be a family trait, based on the time we met his sister.) In "Hill Street Station," we get to see the first "Hi ma" call with his usual collar and we also get to see the absolute glee on his face when he leaps off a desk to join a pile against a suspect gone mad, even though Furillo warns him, "No biting!" You can see his disappointment as he tells his captain that it isn't fair. "One lousy nose and I'm branded for life." Eventually, without losing his color, he managed to get a wife and child too. I even confess: When I was exiled in seventh and eighth grade in an awful northeastern Kansas town (but isn't seventh and eighth grade hell no matter where you are?), I often growled like Belker at the jerks in junior high. According to Bochco's DVD commentary, part of the reason Weitz won the part was that during the audition he leaped off a desk shrieking and growling and he scared the late Grant Tinker, whose production company MTM produced Hill Street Blues, so much that he didn't want to tell him if Weitz didn't get cast. If you recall, the MTM production company logo was a cat (like MGM's Leo the Lion) in a circle meowing. For Hill Street Blues, the kitty wears a policeman's cap. For St. Elsewhere, the cat would have a doctor's surgical cap and mask (and in that show's final episode, the cat would be hooked up to a heart monitor and then flatlined when the credits finished). For Newhart, Bob Newhart would do the meowing.

According to Bochco's DVD commentary, part of the reason Weitz won the part was that during the audition he leaped off a desk shrieking and growling and he scared the late Grant Tinker, whose production company MTM produced Hill Street Blues, so much that he didn't want to tell him if Weitz didn't get cast. If you recall, the MTM production company logo was a cat (like MGM's Leo the Lion) in a circle meowing. For Hill Street Blues, the kitty wears a policeman's cap. For St. Elsewhere, the cat would have a doctor's surgical cap and mask (and in that show's final episode, the cat would be hooked up to a heart monitor and then flatlined when the credits finished). For Newhart, Bob Newhart would do the meowing.

I loved this show so much that I could probably write lengthy paragraphs about all its characters, including recurring ones, but then this piece would likely never end (or even more likely I'd miss my own deadline of the show's 30th anniversary), so I'm going to keep concentrating on that "Hill Street Station" installment to focus on the characters most pivotal to its developments. The main representatives of the beat cops on the show were the partners Bobby Hill and Andy Renko (Michael Warren, Charles Haid). Bobby was a laid-back, African-American officer who in the second season is upset when the black policemen's organization elects him vice president in absentia. He doesn't want anything to do with politics, but the other black members of the group tell him they picked Bobby precisely because of his nonthreatening demeanor that they feel they can use to pressure the department into promoting more black policemen. Renko always seems to have a run of bad luck and, though Hill Street Blues takes place in an unnamed urban

city (Bochco says it was loosely based on Pittsburgh, but second unit scenes were shot in Chicago), seems to have a redneck air about him. One of the calls the partners answer in the premiere is a domestic disturbance where a mother prepares to wield a knife on her towel-wearing teen daughter because she caught her bedding her husband, who is hiding in the bathroom. Bobby manages to defuse the situation, but when he and Renko return to the street, they find their squad car stolen. They search in vain for a working pay phone to call it in and then comes the most shocking and dramatic moment of the show. As they enter a building, they stumble upon some drug dealers who open fire, leaving Hill and Renko lying bleeding on the floor. The original plan was for Renko to die, but the pilot Charles Haid had filmed didn't get picked up, so they made a change and he lived. It's an interesting parallel to Bochco's later series NYPD Blue where Dennis Franz's character Andy Sipowicz (Renko and Sipowicz had the same first name. Weird.) also got shot in the premiere and was slated to die but they changed their mind then too. (Franz, by the way, played two characters on Hill Street: the corrupt Detective Sal Benedetto and later as a regular, the colorful Detective Norman Buntz.) It was an easier fix than Joe Coffey though. They not only shot him in an episode, they showed a chalk outline where his body had been only to bring him back to life.

city (Bochco says it was loosely based on Pittsburgh, but second unit scenes were shot in Chicago), seems to have a redneck air about him. One of the calls the partners answer in the premiere is a domestic disturbance where a mother prepares to wield a knife on her towel-wearing teen daughter because she caught her bedding her husband, who is hiding in the bathroom. Bobby manages to defuse the situation, but when he and Renko return to the street, they find their squad car stolen. They search in vain for a working pay phone to call it in and then comes the most shocking and dramatic moment of the show. As they enter a building, they stumble upon some drug dealers who open fire, leaving Hill and Renko lying bleeding on the floor. The original plan was for Renko to die, but the pilot Charles Haid had filmed didn't get picked up, so they made a change and he lived. It's an interesting parallel to Bochco's later series NYPD Blue where Dennis Franz's character Andy Sipowicz (Renko and Sipowicz had the same first name. Weird.) also got shot in the premiere and was slated to die but they changed their mind then too. (Franz, by the way, played two characters on Hill Street: the corrupt Detective Sal Benedetto and later as a regular, the colorful Detective Norman Buntz.) It was an easier fix than Joe Coffey though. They not only shot him in an episode, they showed a chalk outline where his body had been only to bring him back to life.

Two regulars actually weren't playing cops. The previously mentioned Barbara Bosson as Furillo's ex-wife Fay became a regular at the urging of Fred Silverman who suggested that the series needed a character who was a civilian so there would be a viewpoint unrelated to the legal system. The other was Veronica Hamel as public defender Joyce Davenport. In his commentary, Bochco says Hamel was the last person cast — they'd already started filming the first episode without a Joyce when Hamel walked in and saved the day. When we meet Davenport, she's storming in to hammer away at Furillo about the treatment of one of her clients who has been lost somewhere in the system. She's a fierce advocate for her client and fiery at what she sees as constant abuse by the actions of overzealous officers. That's why the ending of "Hill Street Station" comes as such a surprise when you see that Frank and Joyce, who have exhibited nothing but rancor at each other throughout the episode, are secret lovers. In fact, most episodes of the series ended with the two in some sort of steamy sexplay. Hamel also got some of the most dramatic moments of a series that tended toward the darkly humorous, ranging from the murder of a

colleague that made her rethink her chosen profession to an episode involving the execution of a client who was convicted and headed to death row and sought her as a witness to his last moments. Travanti and Hamel had great chemistry and one of the biggest mysteries to me since Hill Street Blues went off the air is where did these talented actors go? IMDb shows that Travanti has done a lot of one episode shots on other series, the most recent being the new version of The Defenders with Jim Belushi and Jerry O'Connell, but he's never had a role post-Hill Street that came close to Furillo. Hamel's career has followed a fairly similar path, with her most recent work being three episodes of Lost. Sadly, some of the cast members are no longer with us. Michael Conrad of course died during the show's fourth season. Robert Prosky, who joined the show as the new dispatch sergeant, Stan Jablonski, died in 2008. Kiel Martin (Detective J.D. LaRue) died of lung cancer in 1990, the same year Rene Enriquez (Lt. Ray Calletano) succumbed to pancreatic cancer. Trinidad Silva (gang leader Jesus Martinez) died in a car wreck in 1988.

colleague that made her rethink her chosen profession to an episode involving the execution of a client who was convicted and headed to death row and sought her as a witness to his last moments. Travanti and Hamel had great chemistry and one of the biggest mysteries to me since Hill Street Blues went off the air is where did these talented actors go? IMDb shows that Travanti has done a lot of one episode shots on other series, the most recent being the new version of The Defenders with Jim Belushi and Jerry O'Connell, but he's never had a role post-Hill Street that came close to Furillo. Hamel's career has followed a fairly similar path, with her most recent work being three episodes of Lost. Sadly, some of the cast members are no longer with us. Michael Conrad of course died during the show's fourth season. Robert Prosky, who joined the show as the new dispatch sergeant, Stan Jablonski, died in 2008. Kiel Martin (Detective J.D. LaRue) died of lung cancer in 1990, the same year Rene Enriquez (Lt. Ray Calletano) succumbed to pancreatic cancer. Trinidad Silva (gang leader Jesus Martinez) died in a car wreck in 1988.The show also was blessed with many guest stars or near regulars playing roles before they achieved fame elsewhere. Some of those actors included: two Larry Sanders Show alums Jeffrey Tambor as a shady lawyer turned cross-dressing

judge, and Megan Gallagher as an officer; David Caruso as the leader of the Irish street gang The Shamrocks; Jane Kaczmarek as an officer; Pat Corley as an overworked and incompetent coroner; Jennifer Tilly as a gangster's moll who dates Henry; Frances McDormand as a public defender with a drug problem; Dan Hedaya as a crooked cop; Lindsay Crouse as a lesbian officer accused of sexual harassment by a hooker; Linda Hamilton as Coffey's girlfriend who is raped; Danny Glover as a former gang leader who returns under the guise of a social reformer; Edward James Olmos as an apartment tenant being harassed by a landlord trying to force his dwellers out so he can raise rates; Alfre Woodard (who won an Emmy for her work) as the mother of a little boy shot to death by mistake by an officer; Ally Sheedy as a senior criminology student that J.D. takes a shine to despite the age gap; and legendary character actor Lawrence Tierney (best known to younger readers as Joe in Reservoir Dogs and Elaine's dad on Seinfeld) as the night shift dispatch sergeant who got the last line of the series, answering the phone and saying, "Hill Street."

judge, and Megan Gallagher as an officer; David Caruso as the leader of the Irish street gang The Shamrocks; Jane Kaczmarek as an officer; Pat Corley as an overworked and incompetent coroner; Jennifer Tilly as a gangster's moll who dates Henry; Frances McDormand as a public defender with a drug problem; Dan Hedaya as a crooked cop; Lindsay Crouse as a lesbian officer accused of sexual harassment by a hooker; Linda Hamilton as Coffey's girlfriend who is raped; Danny Glover as a former gang leader who returns under the guise of a social reformer; Edward James Olmos as an apartment tenant being harassed by a landlord trying to force his dwellers out so he can raise rates; Alfre Woodard (who won an Emmy for her work) as the mother of a little boy shot to death by mistake by an officer; Ally Sheedy as a senior criminology student that J.D. takes a shine to despite the age gap; and legendary character actor Lawrence Tierney (best known to younger readers as Joe in Reservoir Dogs and Elaine's dad on Seinfeld) as the night shift dispatch sergeant who got the last line of the series, answering the phone and saying, "Hill Street."Lots of television shows had good and great acting, even if the series themselves weren't that special. What set Hill Street Blues apart was what went on behind the scenes. Its creators, writers and directors who changed the medium with its structure and storytelling. It doesn't seem like that radical an idea to have story

arcs that ran over multiple episodes, but bringing that form to a police drama was revolutionary. It paved the way for the technique to be used in other Steven Bochco series such as L.A. Law which took the format to a law firm; the short-lived Bay City Blues which tried it out on a minor league baseball team; and Murder One, which attempted to cover a single murder trial over the course of an entire season. Other non-Bochco shows that found the freedom to embrace the large cast/dark humor/multiepisode arc in the medical world (St. Elsewhere) or much later to paint a portrait of an entire city (The Wire). Some of the writers who worked on Hill Street would go on to make their own cultural landmarks such as Anthony Yerkovich, who would create Miami Vice; Mark Frost, who would co-create Twin Peaks; Dick Wolf, who birthed the Law & Order empire; and, of course, David Milch, who would not only create NYPD Blue for Bochco but the incomparable Deadwood. Even Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright David Mamet wrote an episode, "A Wasted Weekend," an unusual entry for the series where the bulk of the action concerned Jablonski, Goldblume, Hill and Renko on a hunting trip.

arcs that ran over multiple episodes, but bringing that form to a police drama was revolutionary. It paved the way for the technique to be used in other Steven Bochco series such as L.A. Law which took the format to a law firm; the short-lived Bay City Blues which tried it out on a minor league baseball team; and Murder One, which attempted to cover a single murder trial over the course of an entire season. Other non-Bochco shows that found the freedom to embrace the large cast/dark humor/multiepisode arc in the medical world (St. Elsewhere) or much later to paint a portrait of an entire city (The Wire). Some of the writers who worked on Hill Street would go on to make their own cultural landmarks such as Anthony Yerkovich, who would create Miami Vice; Mark Frost, who would co-create Twin Peaks; Dick Wolf, who birthed the Law & Order empire; and, of course, David Milch, who would not only create NYPD Blue for Bochco but the incomparable Deadwood. Even Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright David Mamet wrote an episode, "A Wasted Weekend," an unusual entry for the series where the bulk of the action concerned Jablonski, Goldblume, Hill and Renko on a hunting trip.On a more general level, what I've found fascinating in the post-Hill Street era is how durable and versatile the police show genre is. When I become a fan of a certain type of show, it's pretty difficult for me to sample another in the same genre because they don't live up. Take the medical drama for example. I loved St.

Elsewhere and so I never understood how anyone could say they liked it and then watched ER, Chicago Hope or Grey's Anatomy. It took Scrubs (which as a comedy was different anyway) and House to break my bias on that and that's because House has a completely different approach to the medical show. It's the same thing on the comedy side. It baffles me how anyone who has ever seen the brilliance of The Larry Sanders Show and its behind-the-scenes look at an entertainment TV show can then watch the terribly overrated 30 Rock and not see it for a pasty pale imitation much in the same way Tina Fey's movie Mean Girls was a defanged Heathers lite. Both pull their punches. The police drama didn't take as long as the medical drama did to find new quality examples after Hill Street that weren't just copies: Cagney and Lacey, Miami Vice, Crime Story, NYPD Blue, Homicide: Life on the Street, all the variations of Law & Order and CSI, The Shield, The Wire (even though its scope was much wider than merely police, that's how it was essentially sold in Season 1) even the short-lived such as Boomtown and much-maligned such as Cop Rock. In its twisted way, Dexter is essentially a police drama. I'm even leaving out ones I've never seen or that I don't care for but others do such as The Closer.

Elsewhere and so I never understood how anyone could say they liked it and then watched ER, Chicago Hope or Grey's Anatomy. It took Scrubs (which as a comedy was different anyway) and House to break my bias on that and that's because House has a completely different approach to the medical show. It's the same thing on the comedy side. It baffles me how anyone who has ever seen the brilliance of The Larry Sanders Show and its behind-the-scenes look at an entertainment TV show can then watch the terribly overrated 30 Rock and not see it for a pasty pale imitation much in the same way Tina Fey's movie Mean Girls was a defanged Heathers lite. Both pull their punches. The police drama didn't take as long as the medical drama did to find new quality examples after Hill Street that weren't just copies: Cagney and Lacey, Miami Vice, Crime Story, NYPD Blue, Homicide: Life on the Street, all the variations of Law & Order and CSI, The Shield, The Wire (even though its scope was much wider than merely police, that's how it was essentially sold in Season 1) even the short-lived such as Boomtown and much-maligned such as Cop Rock. In its twisted way, Dexter is essentially a police drama. I'm even leaving out ones I've never seen or that I don't care for but others do such as The Closer.

Hill Street Blues' lasting legacy remains as the starting point for the higher level of quality drama that has continued to get better to this very day. Television always has been good at comedy, if not challenging or topical until All in the Family, but the best TV dramas before Hill Street usually were anthologies such as The Twilight Zone with different stories each week or just generally entertaining such as Columbo (on which Bochco served as a writer and story editor in the early seasons) or The Rockford Files, but hardly challenging. Lou Grant did get into some issues, but imagine how interesting a newspaper drama made in the Hill Street template could have been. Since Hill Street Blues hit the air, even though it slipped in its last couple of seasons, it seems as if there's always been some quality drama on and when cable exploded, it's been a smorgasboard where now the situation is reversed and television (non-network at least) does drama better than it does comedy. Perhaps this is because Hill Street Blues showed artists that you didn't have to be only purely drama or purely comedy and series such as The Sopranos, Deadwood, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, etc., satisfies the audience's need for both.

Hill Street Blues, aside from the technology, hasn't aged much when you watch it today because it tells stories about people you care about and spins tales that capture your attention and seldom lets go. Except in the weaker later years, I can't recall any storylines that were real duds as is often the case in the best of

shows (think Donna and Medavoy on NYPD Blue, the "D Girl" episode of The Sopranos, James' noir excursion in season 2 of Twin Peaks). Re-watching some of its key episodes, I still marvel at the ability of Hill Street to shift emotional gears so fast and so smoothly, cracking you up in one scene then touching your heart in the next. Not every show can treat death as both profound and absurd like Hill Street did, going serious with an execution or certain murders and then having a character drop dead in his plate of food at a fundraiser or a politician plunging through a high-rise window screen while trying to score points by taking the press on a tour of the building's deplorable conditions. It could even combine them, taking the comic team of Belker and the crazy Captain Freedom and breaking your heart when Freedom dies while staying in his dementia until the end. Remember, the power is in the glove. It always was. Even Sgt. Esterhaus didn't get a break. It must have been heartbreaking to the cast and crew to lose the actor Michael Conrad, but that didn't prevent them from letting Phil check out while having another session of strenuous sex with the insatiable Grace.

shows (think Donna and Medavoy on NYPD Blue, the "D Girl" episode of The Sopranos, James' noir excursion in season 2 of Twin Peaks). Re-watching some of its key episodes, I still marvel at the ability of Hill Street to shift emotional gears so fast and so smoothly, cracking you up in one scene then touching your heart in the next. Not every show can treat death as both profound and absurd like Hill Street did, going serious with an execution or certain murders and then having a character drop dead in his plate of food at a fundraiser or a politician plunging through a high-rise window screen while trying to score points by taking the press on a tour of the building's deplorable conditions. It could even combine them, taking the comic team of Belker and the crazy Captain Freedom and breaking your heart when Freedom dies while staying in his dementia until the end. Remember, the power is in the glove. It always was. Even Sgt. Esterhaus didn't get a break. It must have been heartbreaking to the cast and crew to lose the actor Michael Conrad, but that didn't prevent them from letting Phil check out while having another session of strenuous sex with the insatiable Grace.What makes me sad is how you don't see reruns of Hill Street Blues on TV anymore. TV Land used to show both it and St. Elsewhere back-to-back until it made the decision to fill its schedule with as much crap as possible. Only the first two seasons are available on DVD, though you can see later episodes for free on IMDb. It's a damn shame. Greatness such as Hill Street Blues must be available for future generations.

Tweet

No comments:

Post a Comment